Trials and Tribulations of Gradeless Biology

Today is April 16th and I woke up to a world coated in ice. I knew at 6AM that school buses were cancelled for the day, and was frankly delighted to have a student-free day to catch up on my marking and other loose ends after a very busy month.

This tweet is what reminded me to put blogging on my to-do list; thanks Matthew and Pete for the little push!

Ideas, lead to writing, which leads to more ideas. (thanks @dougpete!). https://t.co/2zAsUotWRj. If you have a few moments at home today, if your school is cancelled, maybe you can write a blog piece?— Matthew Oldridge (@MatthewOldridge) April 16, 2018

So, what to write about? I have so many things I'd like to share; sometimes this causes me to write very LONG posts that touch on lots of different things. Today, inspired by the post/thread above, I've decided to focus on just one thing. That way, I'll have to blog more often to get the rest of my ideas out, right? We'll see. It's still a long post. :)

Grade-less in Biology

This semester I am teaching grade 11 Biology for the first time in quite a few years. It's a nice change of pace from Chemistry, and gives me a different look at what a feedback-focused classroom in secondary science looks like.

Initially, my students seemed receptive to the idea of our class being 'gradeless.' Interesting, since their responses to a survey the first week indicated that they were grade-focused:

It's not surprising that they are grade-focused. Many of these students have their hearts set on careers in healthcare; my classroom is full of future doctors, veterinarians, dentists, and surgeons.

As a result I was not surprised when students were aghast when I returned their first traditional assessments without numbers on them. There was a chorus of 'how will I know how I did?' They were not accustomed to getting feedback without grades. They were accustomed to getting good grades. They were craving the number that would tell them they were good enough.

Many of these students expect senior science courses to be difficult and somewhat unpleasant; they associate rigour with suffering, and many can barely process my repeated invitations to enjoy what they are learning.

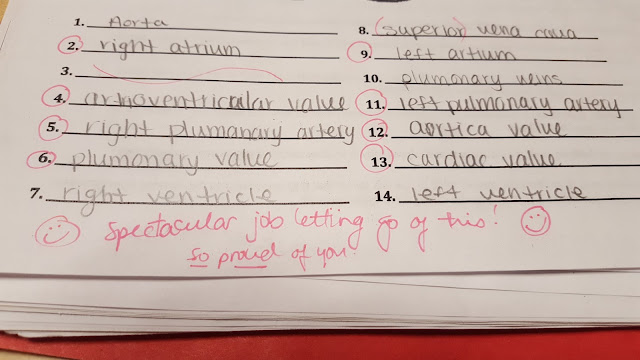

One student, a serial high-achiever, was having hard week just before March break. She declared in frustration that she did not have time to learn the parts of the heart before our quiz that Thursday.

"OK," I said, "then don't."

This stopped her in her tracks. She could not comprehend my answer. She expected me to tell her to suck it up. And, when she didn't learn the parts of the heart, I knew how hard it had been for her to let go of this because I used to be just like her.

I am acutely aware that I am creating discomfort in my classroom. I invite students to share their discomfort and concerns with me; some do, some don't.

Before our interim reports were handed out - just after March Break - I sat down with each student to look at their progress and discuss a grade 'range' that was reasonable based on what they had shown me so far. These conversations went well; many students are on track to reach the goals they have set; others have the chance to identify areas they need to work on to get there. These conferences are what helps me continue moving forward; I know my students better than I have in the past and I am enjoying the new nature of my relationship with them - less an evaluator and more a mentor.

I have often said that I could not have made a change like this 5 years ago. Doing something drastically different is not for the faint-hearted. Taking a leap requires a significant amount of confidence that can only come with experience (and age?) as well as strong support from supervisors and colleagues. This semester my confidence in what I'm doing was finally put to the test.

My schedule on parent-teacher(-student) conference night was quite full. I was full of nervous excitement, wondering about what questions I might get from parents about assessment practices in my class. I had been met with some curiosity first semester but was not questioned or challenged in any real way. This semester, I had communicated much more clearly with parents about the grade-less approach, but had yet to face any questions. The nature of grade 11 Biology had me thinking that I might have more questions at interview time, and I was right.

That evening I answered lots of questions about the grade-less nature of our classroom from parents; some of them eyed me skeptically but, I believe, could see that my intentions were good and that this 'experiment' wasn't doing their children any harm. Finally, I knew I had found the challenge I was anticipating when a serious-looking couple entered the room. One of them held a sheaf of paper which I recognized as all of the written assessments that had been returned to their child with feedback so far this semester. I smiled and invited them to sit down, my heart fluttering with anticipation. This would be my greatest challenge yet.

Parents know their kids really well. These parents - like all parents - had concerns that were really more about their child's wellbeing than anything. Their child was a high achiever and was having trouble understanding how they were 'doing' in Biology. The student was uncomfortable not seeing grades on their work. And, finally, with a certain amount of restrained anger - certainly detectable displeasure - one of them asked the 'big' question:

"Can you explain this...'technique'...you're using?"

I took a deep breath and gave the best 3-minute explanation I could, citing the improved focus on learning that I was seeing in my classes. I shared my desire to have my students learn to look for personal areas of improvement rather than being satisfied with a mark I had assigned. I spoke about students' reluctance to take risks and share creative ideas when they were concerned about grades.

Not much reaction.

Next came something else I had anticipated - the parents shared that they both had post-secondary degrees in Science - they 'knew' what it was like after high school and had serious doubts about the suitability of a grade-free class to prepare their child for that future.

Our conversation got more personal after that. I shared that I had always done well at school. That I, like them, had a post-secondary Science degree. I spoke about how few of my teachers took time to make Science come alive for me, and about how I learned to game the system early on. I reminded them that feedback is rare in large first-year courses at university, and about how much we all had to rely on self-assessment to really know if we were prepared for midterms and finals.

In the end, met with some reluctant acceptance of my 'methods,' I shook hands with them. I acknowledged that I had caused discomfort for their child (and for them) and encouraged them - in particular, their child - to be more honest about this discomfort in the future. Before that evening, their child had never expressed any negative feelings towards what we were doing, and I promised to do my best to ensure we maintained an honest line of communication going forward. Right up to the end, there were no smiles from them, but I've learned to accept that sometimes it's OK to be the only one smiling.

-----

It felt good to be challenged and defend my position. It didn't feel good to be reminded that students don't always share what they are thinking. I ended the night with a good feeling, overall, and feel that this challenging conversation was an important part of my growth as a professional.

Keep doing the good work, everyone! More soon.

Amazing! I was that kid, too, and I can always spot her in my classes. I really wish that I had been given the chance as a student to work in a gradeiess context, at least at some point. I think the idea of sitting with students and talking about where they're at, and what they think they've achieved is so valuable. I have a kiddo in Grade 11 this year, and he made a comment last night at dinner about how much he prefers classes where he really feels like the teacher engages with the particular group of learners, rather than feeling like he is one of the interchangeable faceless students passing in and out of the factory model. I think this is the ultimate example mutual engagement. Thanks for giving me hope.

ReplyDeleteThanks for your words. Sharing is difficult sometimes; I can't see going back to my old ways now, but have lots of work to do re: sharing with my colleagues.

DeleteTell your son to share that positive feedback with his teachers when he feels safe doing so. His words can encourage the ones who are really 'seeing him and might encourage them to share more widely.